Total Quality Management

The Right Stuff: What it takes to champion quality improvement initiatives.

All organizational improvement programs have one thing in common: their success depends on the effectiveness of many collective efforts, rather than any single or individual heroic effort. Contrary to what many managers think, this collective effectiveness cannot be dictated, facilitated, delegated, or otherwise achieved in any instance through direct managerial action alone. This collective effectiveness can only be inspired, balanced and sustained – indirectly – through the operating environment’s ethics and culture, with management as its champion. When managers are champions of projects, some things get done. When managers are champions of improvement programs, some more things get done. But when managers champion the culture, a much bigger thing happens. The projects, the programs, the quality journey over time, and the organization, all flourish, and the firm truly transforms itself into a higher quality organization.

Total Quality Management Defined

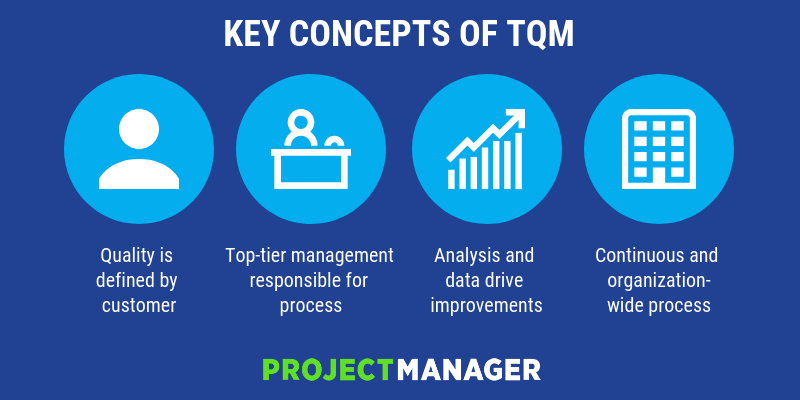

TQM is an approach to organizational performance improvement that is distinguished from other approaches by its key word “total,” which emphasizes a holistic or “total” approach to the firm’s improvement program. TQM’s holistic focus is unique in that it truly focuses on the well being and excellence of the entire enterprise as well as the larger system which the enterprise operates in. TQM is also unique among improvement philosophies because of its ethic of inclusiveness, as TQM truly includes everything and everybody in its mission including: all employees, all stakeholders, all suppliers and especially all customers (both internal and external). Here are three definitions with some key principles underlined that capture the essence of TQM:

- TQM is an economic philosophy, or a strategic intent, to improve the value of the firm by improving the satisfaction of internal and external customers, suppliers, and stakeholders.

- TQM is a 360 degree continuous improvement program of metrics, information, training, analysis, discretionary investments, process improvements, change, and controls, that involve the entire organization.

- TQM is an organization wide management system that applies tools, technologies, and standardized procedures to integrate efforts, to prevent failure costs, to improve process execution, to assure the existence of a capable and supportive organizational culture, and to sustain the organization’s quality journey over time.

From the above definitions, TQM is not just about boosting the bottom line by improving or streamlining a few economic processes. Instead TQM is about boosting the bottom line by doing the right things right, everywhere, for everyone involved, the first time every time. Described in this way, TQM is also an ethic for achieving organizational excellence.

However noble TQM’s philosophies and ethics are, it still must face and overcome the same implementation rigors any improvement program must face. Below are four stages that organizations have typically experienced when implementing TQM.

TQM’s Four Critical Stages

Stage One: The Leadership Stage.

- Leadership must live the philosophy and ethics of TQM. There is no room for selfishness, moral exclusion, exorbitant compensation for a few, scapegoating, abusive management styles or policies, or inconsistent or selective ethics. The philosophy (like any worthwhile ethic) must be universally applicable to all. This may seem easy enough, yet this ethic has proven to be one of the weakest links in many TQM initiatives. TQM truly begins with, and succeeds or fails because of, the strength of this ethic in the practicing organization.

- Without a deep commitment from the top to develop a healthy culture based on win-win fairness, open communication, shared information and teamwork, most organizations will not get very far in TQM. One of the greatest lessons of TQM is not how the lack of good culture kills TQM, but how these deficiencies will constrain or kill any improvement program regardless of their name (including Six-Sigma, Balanced Scorecard, Baldrige, etc).

- This stage generally begins with training the upper and middle management on the general concepts of TQM, and the formation of basic structures to support TQM such as executive steering committee, metrics to aid project targeting (such as Cost of Quality) and a project management system to approve and administer projects.

Stage Two: The Initiation Stage.

- This is always an exciting stage in TQM, as it awakens the organization to all kinds of amazing discoveries about how it can improve itself. Initial projects hit pay dirt with the harvesting of “easy fruit” resulting in reduced waste, lower failure costs, fewer hassles and negative experiences, and happier internal and external customers.

- The culture is energized into new forms of teamwork. Ethics advance dramatically as individuals and departments become more aware and empathetic to the effects they have on others around them. People are not concerned about rewards, as the improvements themselves are delivering intrinsic and non-monetary rewards to all involved.

- Economically, project successes and clear economic dividends makes management’s continued investment in the program justified. Monetary rewards are provided to both individuals and groups, which are perceived as “icing on the cake.”

- There is an abundance of praise for everybody, as everybody kicks their efforts up a notch in a atmosphere of exuberance and mutual sacrifice. .

Stage Three: The Decline Stage

- Unfortunately TQM often goes downhill from here. The reason: burnout. As “easy fruit” projects dry up, increasingly more difficult targets are attempted that often tax and degrade TQM’s delicate system of ethics, rewards and efforts.

- As project difficulty increases it becomes more difficult to do the ethics stuff, such as inclusion, dialog, consensus, win-win, etc as each of these take effort. Narrower objectives start getting priority over the cultural requirements, and these objectives generally benefit progressively narrower stakeholder groups. These efforts may offer greater economic potential than the earlier projects, and require the efforts of many stakeholders to implement, but upon successful completion these projects tend to distribute rewards to fewer participants and beneficiaries, reinforcing fewer efforts for the next project. This contributes to an ethics and rewards deficit in the culture, increasing resistance to change, and fermenting and a form of mental or spiritual burnout where many hearts simply “are not in it” any more, making some key players not as willing as they once were.

- Another form of “burnout” is a physiological form that actually makes many past supporters progressively less capable of supporting new initiatives. It takes a lot of human energy to initiate a quality journey (improvement trend) in an organization, and it takes even more to sustain it. This is a common problem with all improvement programs. It simply is humanly impossible to sustain the required energy level indefinitely without learning how to work smarter, not just harder. Also, rewards must be commensurate to the effort, not just the results, or a declining state of reduced effort will set in all the faster. This understandably runs counter to the “reward the results” mentality popular in management today. If people are physiologically burned out all rewards become less relevant and some become completely irrelevant. Research in the construction industry indicates that workers can lose up to 50% of their productivity or more when they are overworked for prolonged periods time. In just a few weeks of excessive stress and exertion, workers can quickly become less productive than what normal efforts in the first place would have produced. This effort constraint is widely recognized today in many fields as a physiological fact, and it’s rate of decline seems to accelerate when people’s hearts are no longer engaged in the objective at hand. It is a common managerial error to demand too much effort (from themselves and/or others) while relying too much on higher rewards for ever fewer participants. This error rate is magnified by the tendency of management to increasingly focus on technical process improvements as project difficulty increases. This effort mismanagement is something every manager needs to be aware of as it is a leading common cause of quality program failure and journey decline. When it comes to sustaining a quality journey, our own OrgCulture Study as well as other studies robustly suggest that human factors such as ethics, culture, risks and rewards, management style and satisfaction, once considered to be the “soft side” of quality, collectively are statistically more relevant to program and journey success over time than technical process improvements. The logic involved is not a choice between one or the other, but that the latter requires the former.

- Stage three is about the organization’s powerful and often inevitable transition from euphoria toward withdrawal as effort mismanagement takes its toll. Without advancements in the quality system infrastructure to help participants cope, and without maintaining cultural balance, people not only become less able but less willing to sustain the journey. This decline in support can also be referred to as a decline in the cultural maturity level of the organization, which can be measured using our Online Survey. If cultural maturity declines, the quality journey will decline in lock-step. Fortunately both conditions are correctable with a little ethics and culture management.

Stage Four: The Journey Perpetuation Stage

- This stage is about slowing down or reversing the natural forces of decline described in stage three. Here, the focus is on helping the organization cope and advance by working smarter (not just harder), and by managing a balancing act between efforts, ethics, rewards and satisfaction with respect to process improvements (not just pushing for technical success in narrower and more complex projects). This results in achieving higher levels of teamwork and integration, which, ironically, make the more complex projects more likely to succeed.

- This stage adopts technologies, advances technical tools, and emphasizes the championing of higher culture practices so appropriate levels of “rational cooperation” are comfortably developed and maintained. Information sharing and ethics and culture practices are integrated so people can get the same information and make the same quality decisions with less physical and psychological effort, and know what they can expect from the system in return. In this stage the focus is on reducing frustration, firefighting, gutter fighting, and negative competition, and maximizing satisfaction and trust for all participants so the organization can fundamentally advance its journey with a maximum of internal cooperation.

- This stage emphasizes ethics and culture as much as its technical quality, and there is a shared intuitive awareness at all levels that cultural excellence and technical process capability are dependent on each other. Quality management is integrated into each process so it can be performed in normal time with normal effort. Employee satisfaction is healthy, and the culture is capable of ramping up and supporting initiatives that matter the most to the organization, its participants and stakeholders. Most importantly, the organization is able to sustain its improvement trend and accomplish its strategic objectives.

Three Leading Causes of Quality Journey Stagnation:

- Lack of continuous effort and focus. Benchmark statistics of the highest quality organizations show the greatest distinguishing factor in achievement was not the brand of programming they chose, but rather how long (in years or decades) they have sustained their continuous effort and focus on quality improvement. Therefore, just “not stopping” and assuring journey continuity may be the single most significant aspect of any quality improvement program. (Has your group’s journey been continuous? If so, for how long)?

- Lack of methodical journey progression. One well documented model, the Capability Maturity Model by SEI (CMM), has statistically correlated the concept of journey progression by organizations. Using the CMM (or Trillium) Models as guides, we can visualize the “logic” of normal progression and generalize that sustainable journey progression could be risked if normal progression patterns common in advancing organizations are not followed or if key maturity level steps are ignored.

The Trillium scale spans levels 1 through 5. The levels can be characterized in the following way:

-

- Unstructured: The development process is ad-hoc. Projects frequently cannot meet quality or schedule targets. Success, while possible, is based on individuals rather than on organizational infrastructure. (Risk – High)

- Repeatable and Project Oriented: Individual project success is achieved through strong project management planning and control, with emphasis on requirements management, estimation techniques, and configuration management. (Risk – Medium)

- Defined and Process Oriented: Processes are defined and utilized at the organizational level, although project customization is still permitted. Processes are controlled and improved. ISO 9001 requirements such as training and internal process auditing are incorporated. (Risk – Low)

- Managed and Integrated: Process measurements and analysis is used as a key mechanism for process improvement. Process change management and defect prevention programs are integrated into processes. (Risk – Lower)

- Fully Integrated: Formal methodologies are extensively used. Organizational repositories for development history and process are utilized and effective. (Risk – Lowest)

For example, if an organization is operating at the Trillium Level #1, it is highly unlikely they will benefit much from an aggressive investment in six-sigma, which tends to succeed best when organizations are already operating at Trillium levels 3 or higher. The key to journey progression is knowing where you are and pursuing the next logical maturity level. (What level is your group at)?

- Lack of Ethics and Culture Management. When organizations attempt to advance quality without advancing ethics and culture they often are spinning their wheels only to wonder later why quality initiatives did not work as well as expected. Trying to improve technical quality issues, such as yield or Cpk without considering possible ethics or cultural causes can quickly limit the available human energy an organization can give to its improvement journey.

The Role of Ethics and Culture in Quality Management: Ethics and Culture are closely related to Quality Improvement and the organization’s Quality Maturity Level. When processes improve, ethics and culture generally improve also, and visa versa. Often ethics are the constraint factor holding back process capability improvement, and sometimes poor process capability encourages poor ethical behavior. Also, managers do not cause improvement projects to succeed as much as they may think they do, at least not directly. It is the operating culture, or the collective effort, that decides which projects succeed or fail in varying degrees. This is where TQM has provide a valuable lesson to all improvement professionals. TQM showed us the importance of people and integrated efforts, the importance of getting the culture behind the improvement initiatives, and the importance of getting management to champion an ethical culture.

Quality and process improvement are not entirely synonymous. The former requires ethics, the latter does not, as the following points demonstrate:

- TQM slipped in popularity in the mid and late 1990’s not because it was inadequate, but because executives, shareholder boards, and in some cases even employees and their unions forced philosophical, ethical and cultural compromises that took a heavy toll on TQM programs. Ethically, the late 1990’s were the “anything goes” years for management, giving rise to alternative quality initiatives that focused more on techno-economic quality gains without constraining management with ethical or cultural standards. The fact that six-sigma and other best practices programs carried no ethics baggage made them popular among executives and trainers. Ironically, many of these now maturing programs are increasingly incorporating the TQM doctrines of the past, such as notions of common courtesy, trust, inclusion, participation, open dialog, consensus, team based rewards, and basic governance standards.

- Process capability improvement alone does not reduce the risk of ethics failure, and ethics failures definitely constrain improvements in process capability. The same kinds of failures that bludgeoned Enron and Arthur Andersen could still occur in any organization regardless of their apparent successes in process improvement. Unless ethical and cultural excellence are incorporated by design into process improvement initiatives (which TQM incorporates), the risks of journey failure (and business failure) remain.

Whether you are doing TQM, or some other quality improvement program, any program stands to benefit by incorporating the ethics of TQM. These ethics are essential for sustaining quality journeys over time because every improvement program depends on collective efforts, and effective collective efforts invariably depend on management’s dedication to ethical and cultural excellence.